# What oil in water coolant means for your engine

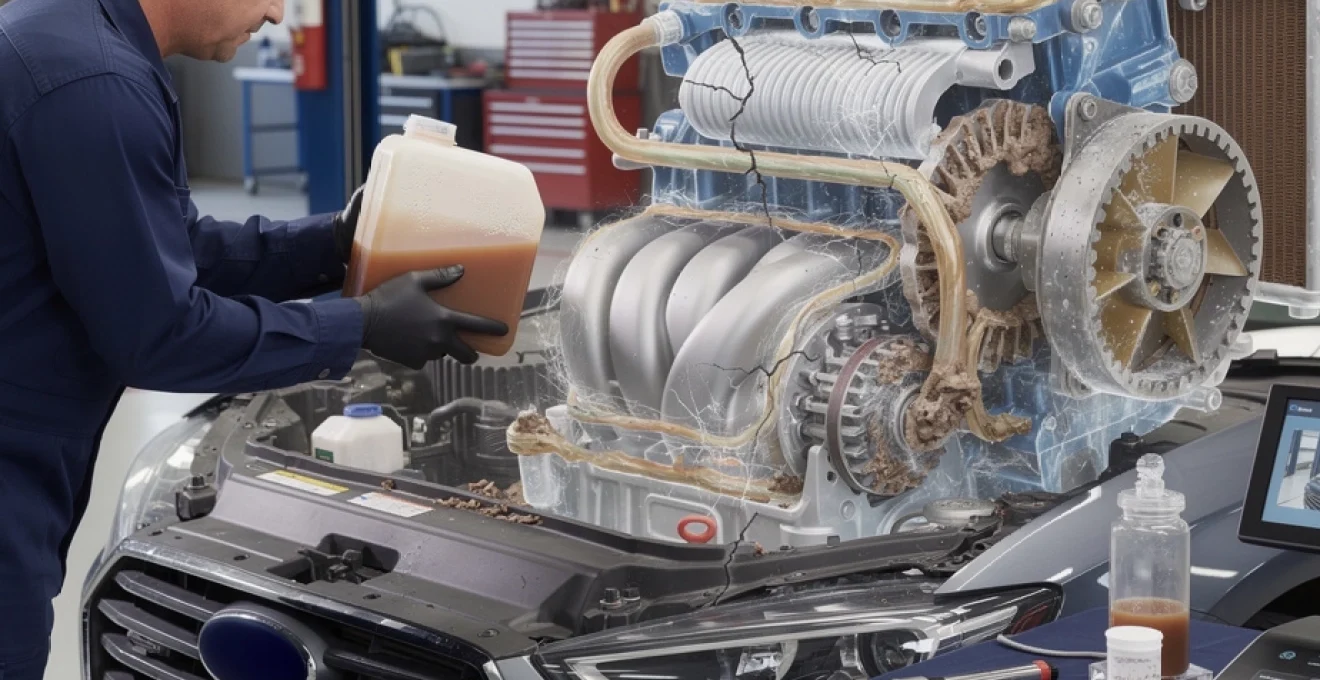

Discovering oil contamination in your vehicle’s cooling system represents one of the most concerning mechanical issues you can encounter. The engine cooling system and lubrication system are designed as completely separate entities, each with distinct functions critical to engine longevity. When these two systems breach their boundaries and intermix, the consequences can range from minor performance degradation to catastrophic engine failure. Understanding the mechanisms behind this contamination, recognising the warning signs early, and implementing swift corrective action can mean the difference between a manageable repair bill and a complete engine replacement. Modern combustion engines operate under increasingly demanding conditions, with tighter tolerances and higher operating temperatures that make them particularly vulnerable to the cascading failures that oil-contaminated coolant can trigger.

How engine coolant contamination with oil occurs in modern combustion engines

The architecture of internal combustion engines features numerous pathways where engine oil and coolant circulate in close proximity, separated only by gaskets, seals, and metal barriers. These components operate under extreme thermal cycling, constant vibration, and substantial pressure differentials that can eventually compromise their integrity. Understanding the primary failure points helps you identify the most likely culprits when oil appears in your cooling system.

Head gasket failure and breach points between oil and coolant passages

The cylinder head gasket serves as one of the most critical sealing surfaces in any engine, maintaining separation between combustion chambers, oil galleries, and coolant passages. This multi-layer component must withstand combustion pressures exceeding 1,000 psi whilst simultaneously managing temperature differentials of several hundred degrees across its surface. When a head gasket fails, it typically does so at its weakest point—often where oil and coolant passages run closest together within the cylinder head and block interface.

Head gasket failure doesn’t always announce itself with dramatic symptoms. In many cases, the initial breach creates a small pathway between oil and coolant circuits before progressing to affect combustion sealing. You might notice the telltale milky residue in your coolant expansion tank weeks before experiencing misfires or white exhaust smoke. The failure mechanism often begins with thermal fatigue from repeated heat cycles, particularly in engines that have experienced overheating episodes or where the cooling system has been inadequately maintained.

Modern multi-layer steel gaskets incorporate various coating technologies designed to enhance sealing performance, but these advanced materials cannot compensate for underlying issues such as cylinder head warpage, incorrect torque specifications during installation, or improper surface preparation. When diagnosing head gasket failure, mechanics look for specific patterns of contamination that indicate whether the breach involves oil-to-coolant transfer, coolant-to-oil migration, or both simultaneously.

Cracked cylinder head or engine block allowing Cross-Contamination

Cylinder heads and engine blocks represent the structural foundation of your engine, manufactured from cast iron or aluminium alloys selected for their specific thermal and mechanical properties. Despite their robust construction, these components can develop cracks that create pathways between separate fluid circuits. Thermal stress represents the primary culprit behind these fractures, particularly in aluminium cylinder heads where the material’s higher thermal expansion coefficient creates greater stress during temperature fluctuations.

Cracks typically propagate along stress concentration points such as valve seats, spark plug bosses, or between adjacent coolant and oil passages. The phenomenon of thermal shock—where a severely overheated engine suddenly receives cold coolant—can accelerate crack formation dramatically. You’ll find that aluminium diesel engine heads prove particularly susceptible to cracking between pre-combustion chambers and adjacent coolant jackets, whilst petrol engines more commonly crack around exhaust valve seats.

Detecting cracks requires specialised equipment including magnetic particle inspection for ferrous materials or dye penetrant testing for aluminium components. Some cracks remain virtually invisible to the naked eye yet create sufficient pathways for oil and coolant to intermix. The repair options for cracked heads or blocks range from specialist welding procedures to complete component replacement, depending on the crack’s location and severity.

Oil cooler heat exchanger seal deterioration and leakage pathways

Many modern engines incorporate an oil-to-coolant heat exchanger to regulate engine oil temperature more precisely

to shorten warm-up times and keep viscosity within an optimal range. This heat exchanger usually takes the form of a stacked-plate or shell-and-tube unit where pressurised oil flows on one side and coolant circulates on the other, separated only by thin walls and elastomer seals. Over time, those seals harden, shrink, or crack, while internal plates can corrode, especially where coolant quality has been poor or replacement intervals ignored.

Once the integrity of the oil cooler is compromised, the higher-pressure circuit will typically push fluid into the lower-pressure one. In most operating conditions, engine oil pressure exceeds cooling system pressure, so oil is driven through microscopic breaches into the coolant stream. This explains why you may see heavy, creamy sludge in the expansion tank without corresponding signs of coolant in the engine sump. Replacement of the oil cooler or its core, followed by meticulous cleaning of the cooling system, usually resolves this specific oil-in-coolant contamination pathway without requiring major engine disassembly.

Intake manifold gasket degradation in v-configuration engines

On many V6 and V8 engines, particularly from the late 1990s and early 2000s, the intake manifold doubles as a coolant crossover between cylinder banks. In these designs, the intake manifold gasket not only seals the air path but also separates coolant passages from adjacent oil galleries and the engine valley. As the gasket material ages, heat cycling and chemical exposure can cause it to shrink, crack, or lose clamping force, creating small leak paths where coolant and oil can interact.

When an intake manifold gasket fails in this way, the symptoms of oil in water coolant can be subtle at first. You might see a slow buildup of oily film in the coolant reservoir, slight coolant loss with no visible external leak, or intermittent misfires on cold start as small amounts of coolant seep into intake ports. Because the failure point sits higher in the engine, it may take longer for contamination to reach critical levels compared with a direct block or head breach. Careful inspection of the intake manifold sealing surfaces, along with pressure testing of the cooling system, helps confirm this diagnosis before more invasive engine work is considered.

Diagnosing oil-contaminated coolant through visual and laboratory analysis

Before committing to major repairs, you need a clear diagnosis of why there is oil in the coolant and how far the contamination has progressed. Visual checks provide quick, low-cost clues, while pressure tests and chemical analyses offer more definitive evidence of internal leaks. Combining these approaches gives you a structured way to distinguish between minor seal failures and serious structural damage such as a cracked block or head.

Milky or chocolate-coloured coolant reservoir appearance

The simplest diagnostic tool at your disposal is your own eyesight. When engine oil mixes with coolant, the two fluids form an emulsion that often appears as a milky, coffee-coloured sludge in the reservoir or radiator. You may also notice thick deposits coating the inside of the expansion tank, rubber hoses, and the underside of the radiator cap, as well as an oily sheen floating on top of the coolant. This “chocolate milk” coolant is one of the most recognisable indicators of oil contamination in the cooling system.

However, not every discoloured coolant sample points to a catastrophic internal leak. Old coolant can darken with age and corrosion products, and using incompatible coolant types can create gel-like deposits that mimic oil-contaminated coolant. To avoid misdiagnosis, you should consider other factors: is the oil level on the dipstick rising, does the engine overheat, or does the heater stop blowing hot air because sludge has restricted flow through the heater core? When several of these signs appear together, the likelihood of genuine oil-in-coolant contamination increases significantly.

Coolant pressure testing with radiator cap testers and block test kits

Once visual evidence suggests contamination, the next step is to evaluate the integrity of the cooling system under controlled pressure. A radiator cap pressure tester allows you to pressurise the cooling circuit to its specified operating pressure, typically between 13 and 16 psi for many modern passenger vehicles. By observing whether the system holds pressure or loses it over several minutes, technicians can determine if there is an internal or external leak. A rapid pressure drop with no visible drips under the car often points toward an internal breach into the oil circuit or combustion chambers.

Complementing this, block test kits (sometimes called combustion leak testers) draw vapour from the radiator neck or expansion tank through a special fluid that changes colour in the presence of combustion gases. If exhaust gases are entering the coolant, the test fluid usually shifts from blue to yellow or green, indicating a head gasket failure or cracked head near a combustion chamber. While these tests do not directly measure oil in water coolant, they help distinguish between different failure modes that can co-exist, such as coolant entering the cylinders as well as oil entering the coolant passages.

Hydrocarbon detection using chemical combustion gas testers

For more precise confirmation of combustion-related leaks, hydrocarbon detection devices measure the presence of unburnt fuel and exhaust by-products dissolved in the coolant. These testers may use infrared sensors or electrochemical cells to quantify hydrocarbon concentration levels in parts per million. Elevated hydrocarbon readings in the coolant strongly implicate a path between the combustion chamber and the cooling circuit, even if head gasket failure symptoms are otherwise subtle. This is particularly valuable in early-stage failures where the engine still runs smoothly and has not yet developed obvious misfires or white exhaust smoke.

Chemical combustion gas testers serve as a bridge between simple workshop tools and full laboratory analysis. They can be deployed quickly, require only small coolant samples or vapour, and provide repeatable results that help monitor whether a leak is worsening over time. When combined with data from compression tests or cylinder leak-down tests, hydrocarbon detection allows you to build a robust case for or against head gasket replacement, rather than relying purely on guesswork based on discoloured coolant alone.

Spectroscopic analysis for petroleum-based contaminant identification

In complex or high-value cases—fleet vehicles, performance engines, or warranty disputes—laboratory-grade spectroscopic analysis offers definitive identification of contaminants in the coolant. Techniques such as infrared (IR) spectroscopy and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) can distinguish engine oil additives, transmission fluid components, or fuel residues within a coolant sample. This level of detail is particularly useful when trying to determine whether the source of contamination is the engine oil circuit, an automatic transmission oil cooler integrated into the radiator, or even a previously used cleaning chemical.

While spectroscopic testing may seem excessive for many everyday vehicles, it becomes cost-effective when it prevents unnecessary engine teardown or confirms that a simpler component, such as an oil cooler, is to blame. Think of it as sending your coolant for a forensic investigation: by knowing exactly what type of oil in water coolant you are dealing with, you can target repairs accurately and avoid replacing parts that are still serviceable. Many commercial laboratories offer such testing with turnaround times of just a few days, making it a practical option when diagnosis is unclear.

Engine damage progression from oil and coolant mixture

Once oil and coolant have mixed, the clock starts ticking on engine damage. Even if the vehicle still drives normally, the contaminated mixture quietly attacks the cooling system, lubrication pathways, and metal surfaces. Understanding how this damage progresses helps you appreciate why continuing to drive with oil in coolant is such a high-risk choice, even for short distances.

Reduced heat transfer efficiency and localised overheating zones

The primary role of coolant is to carry heat away from the engine block and heads to the radiator, where it can be dissipated. When coolant becomes emulsified with oil, its thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity both decrease, meaning it absorbs and releases heat less effectively. Imagine wrapping the inside of your cooling system in a thin, insulating layer of grease—that is essentially what emulsified oil does. The result is uneven temperature distribution, with hot spots forming around exhaust ports, combustion chambers, and thin casting sections.

These localised overheating zones can warp cylinder heads, distort sealing surfaces, and accelerate head gasket deterioration. Over time, you may see symptoms such as intermittent temperature spikes, a cooling fan that runs more frequently, or a heater that alternates between hot and lukewarm as sludge moves around the system. Left unchecked, this reduced heat transfer efficiency sets the stage for major failures, including dropped valve seats, cracked heads, and even piston seizure in extreme cases.

Coolant pump impeller erosion and circulation system blockages

The water pump relies on clean, correctly mixed coolant to lubricate its internal bearings and maintain efficient impeller operation. When the coolant is laden with abrasive particles, sludge, and oil emulsion, the pump’s impeller and seals begin to suffer. Plastic impellers can erode or crack, while metal impellers and housings may corrode faster as protective additives in the coolant are depleted. As pump efficiency falls, circulation slows, further compounding the overheating risk.

At the same time, thick deposits can accumulate in narrow passages, particularly in heater cores, small-diameter hoses, and the by-pass circuits around the thermostat. Eventually, these blockages act like cholesterol in an artery, restricting flow until certain parts of the engine receive barely any coolant at all. You might notice the cabin heater failing first because the heater matrix often clogs before the main radiator does, serving as an early warning that coolant flow is compromised by oil contamination.

Radiator core fouling and decreased thermal dissipation capacity

Radiators are designed with fine tubes and delicate fins to maximise surface area for heat exchange. When oil in water coolant passes through these tubes, sticky residues adhere to the internal walls and trap additional dirt, metal particles, and corrosion products. Over time, this fouling layer acts like limescale in a kettle, drastically reducing the radiator’s ability to shed heat. Even with a functioning thermostat and water pump, the engine may run hotter than normal because the radiator is effectively strangled from the inside.

External contamination can compound the problem. Oil mist vented from the crankcase or external leaks can coat the outside of the radiator, attracting dust and forming an insulating blanket on the fins. When internal and external fouling occur together, the net thermal dissipation capacity of the radiator can drop by 30–50% or more, depending on severity. In many cases of prolonged oil-in-coolant contamination, replacing the radiator becomes more cost-effective than attempting to flush and restore it to full efficiency.

Bearing and camshaft lubrication compromise from emulsified oil

Oil and coolant do not only mix in one direction. In many failures, coolant also finds its way into the engine oil, either through the same breach or by gravity as emulsified mixture drains back to the sump. When coolant contaminates the oil, its ability to maintain a stable lubricating film between moving parts is severely reduced. Bearings, camshafts, lifters, and turbocharger shafts rely on a precise oil viscosity and additive package; introduce water and glycol, and that carefully engineered balance collapses.

The result is often a grey, foamy sludge on the dipstick and under the oil filler cap, accompanied by increased valvetrain noise, low oil pressure warnings, or in worst cases, spinning of main or rod bearings. Once bearing surfaces are damaged by metal-to-metal contact, repairs escalate from a straightforward gasket replacement to a full engine rebuild or replacement. This is why many professionals recommend shutting the engine down immediately once you suspect coolant has infiltrated the lubrication system, rather than attempting to “nurse” the vehicle home.

Repair solutions for oil-in-coolant contamination issues

Effective repair of oil-in-coolant contamination requires addressing both the root cause and the resulting sludge throughout the system. Simply flushing the coolant without repairing the breach will only provide temporary relief, as fresh coolant will quickly become contaminated again. The appropriate solution depends on whether the failure originates from gaskets, structural cracks, or auxiliary components such as oil coolers and intake manifolds.

In many cases, the first step is a thorough diagnostic work-up: pressure testing, hydrocarbon detection, and visual inspection to pinpoint the source. For failed oil coolers, replacement of the cooler unit or its seals is often relatively straightforward, followed by multiple cooling system flushes using a dedicated detergent-based cleaner to remove residual oil. When intake manifold gaskets are at fault, resealing the manifold with updated gasket materials and correct torque procedures can permanently resolve the issue, provided no secondary damage has occurred.

Head gasket replacement and cracked head or block repairs represent the more involved end of the spectrum. These procedures typically require significant disassembly, precise surface machining, and careful reassembly using manufacturer torque sequences and angles. In some situations, especially when an engine has been badly overheated or run for a long time with contaminated oil, replacing the entire engine or long block may be more economical than rebuilding. Regardless of the chosen path, always pair major mechanical repairs with fresh engine oil, filter, and a complete coolant system decontamination to ensure that no residual sludge shortens the life of the newly installed components.

Preventative maintenance strategies to avoid coolant system oil ingress

Given how costly oil-in-coolant contamination can become, prevention is far more attractive than cure. Regular maintenance does more than tick a box in your service book—it actively extends the life of seals, gaskets, and metal components that separate oil and coolant circuits. By adopting a proactive approach, you significantly reduce the risk of sudden failures that leave you facing an unexpected head gasket job or engine replacement.

Start with the basics: adhere to your vehicle manufacturer’s recommended coolant change intervals, and always use the specified coolant type and concentration. Modern organic acid technology (OAT) and hybrid coolants contain corrosion inhibitors tailored to the alloys used in your engine; mixing the wrong types or running plain water accelerates corrosion and undercuts gasket life. Regularly inspect hoses, expansion tanks, and the radiator cap for signs of deterioration, as these inexpensive parts play crucial roles in maintaining correct system pressure and temperature.

- Monitor engine temperature and heater performance; unexplained rises or loss of cabin heat may signal early circulation issues.

- Check coolant and oil levels monthly, looking for unexplained loss or signs of cross-contamination such as milky residue.

- Avoid aggressive overheating events by stopping the engine promptly if the temperature gauge enters the red or warning lights appear.

- Have the cooling system pressure-tested during major services, especially on higher-mileage vehicles or those used for towing.

Finally, remember that gentle driving habits during warm-up, avoiding repeated short trips, and allowing turbocharged engines to cool down after hard use all reduce thermal stress on gaskets and castings. Think of it as giving the engine time to expand and contract gradually rather than shocking it with abrupt temperature swings. These simple practices, combined with quality fluids and timely maintenance, form a robust defence against oil and water coolant ever meeting in the first place.

Cost implications and insurance considerations for oil coolant contamination repairs

When oil contamination in the coolant is confirmed, one of the first questions that arises is: how much will this cost to fix? The answer varies widely depending on the cause and the extent of secondary damage. Replacing a failed oil cooler and flushing the cooling system might fall in the lower range of repair costs, often comparable to a major service. In contrast, head gasket replacement, cracked head repairs, or engine replacement can escalate into four-figure sums, especially on modern, tightly packaged engines with complex timing systems.

Labour makes up a significant portion of these expenses. For example, some transverse V6 engines require removal or partial lowering of the engine and subframe to access cylinder heads, dramatically increasing hours billed. In addition, consumables such as new head bolts, gaskets, coolant, oil, filters, and cleaning chemicals add to the final bill. In severe cases, ancillary components like radiators, heater cores, or rubber hoses may also need replacement because they are saturated with oil sludge that cannot be reliably flushed out.

What about insurance or warranties—can they help offset these costs? Standard motor insurance policies rarely cover mechanical failures such as head gasket issues unless they result directly from an insured event like a collision. However, extended warranties, manufacturer goodwill programmes, or aftermarket mechanical breakdown insurance may contribute if the vehicle meets their age, mileage, and service-history criteria. Maintaining a complete, documented service record significantly strengthens your position when seeking such assistance.

For fleet operators or owners of high-value vehicles, it can be worth exploring specialised mechanical breakdown cover that explicitly includes internal engine failures and cooling system components. Even if such cover carries a higher premium, the financial protection against a major oil-in-coolant contamination event may prove invaluable over the vehicle’s lifetime. In every case, early diagnosis and prompt action tend to reduce both the direct repair bill and the indirect costs of downtime, rental vehicles, or lost business use, underscoring why you should never ignore the first signs of oil in your coolant.